26 March, 2020

The introduction of the information disclosure and arbitration provisions under Part 23 of the Australian National Gas Rules in August 2017 has resulted in an unsuitable asset valuation methodology, the so-called ‘recovered capital method’ (RCM), becoming the default valuation methodology to be used in arbitrations involving gas pipelines and their users (shippers). This is because it is incompatible with price formation in workably competitive markets, a concept which underpins the objective of Part 23.

The default status of the RCM under Part 23 arguably says more about the short term political and regulatory imperative to reduce delivered gas prices in a supply constrained environment, rather than good regulatory design focussed on producing sensible price signals and facilitating robust commercial outcomes in relation to future investment in and use of Australian gas transmission pipelines. As a result, as part of the current COAG Energy Council review of Part 23, we consider that it should be removed from the NGR

The prescribed objective of Part 23 of the National Gas Rules (the NGR) is to facilitate access to non-scheme gas pipeline services on reasonable terms, which is taken to mean at prices and on other terms and conditions that, so far as practical, reflect the outcomes of a workably competitive market.[1]

Part 23 (Division 4) establishes an arbitration process to resolve any access disputes that arise in relation to the services of these pipelines. However, it is not prescriptive regarding the asset valuation methodology to be applied.

Rather, the value of any assets used must be determined using an asset valuation technique that is consistent with the workably competitive market objective and unless inconsistent with this objective, should be calculated using the RCM.

Atypically, the RCM is a cost-based valuation approach that uses initial pipeline construction cost, which is then adjusted to reflect historical net revenues of the pipeline. This revenue adjustment is intended to reflect the extent of recovery of the pipeline’s capital base from its construction date based on its past profitability.

This historical net revenue-based feature of the RCM is unusual in Australian regulatory practice because (like price formation in workably competitive markets) regulatory pricing is generally forward looking rather than backward looking, with historical revenue recovery not relevant in establishing the regulatory asset base value.[2]

Workable competition is not a concept that guarantees sellers will obtain prices which recover their capital and operating costs, or that buyers will pay prices that preserves some prior level of profitability. In simple terms, the price and quantity outcomes of the competitive market process, which is dynamic rather than static, will reflect the balance of supply and demand.

An expected outcome of a workably competitive market for gas pipelines services is one reflecting the fact that the contracting parties will have substitutes or alternatives open to them, both when the pipeline is first constructed, as well as when pipeline capacity is subsequently re-contracted. Hence, sunk investments by each party should not leave either vulnerable to opportunistic behaviour by the other party, nor affect the negotiated price.

Looking back in the way envisaged by the RCM is contrary to the normal operation of workably compettive markets, in which market participants make decisions based on opportunity cost (the best alternative foregone), which is an inherently forward looking concept.

Further, the differences between expected (and uncertain) returns on investment compared to actual returns cannot be readily reconciled; a difficulty that exists quite apart from the difficulty of ascertaining the original required investment return to be applied ex post, which almost certainly will not be the weighted average cost of capital generally adopted by economic regulators.

Simply because a pipeline investment, which was commissioned in a workably competitive environment for pipeline development, may have secured better (worse) returns than originally expected is not a valid basis to discount (increase) future expected prices, as suggested by application of the RCM.

This can be most clearly seen for pipelines that have been significantly under-utilised since construction and which will have incurred potentially large net revenue shortfalls under the RCM, which must be capitalised into the pipeline’s asset base under that approach.

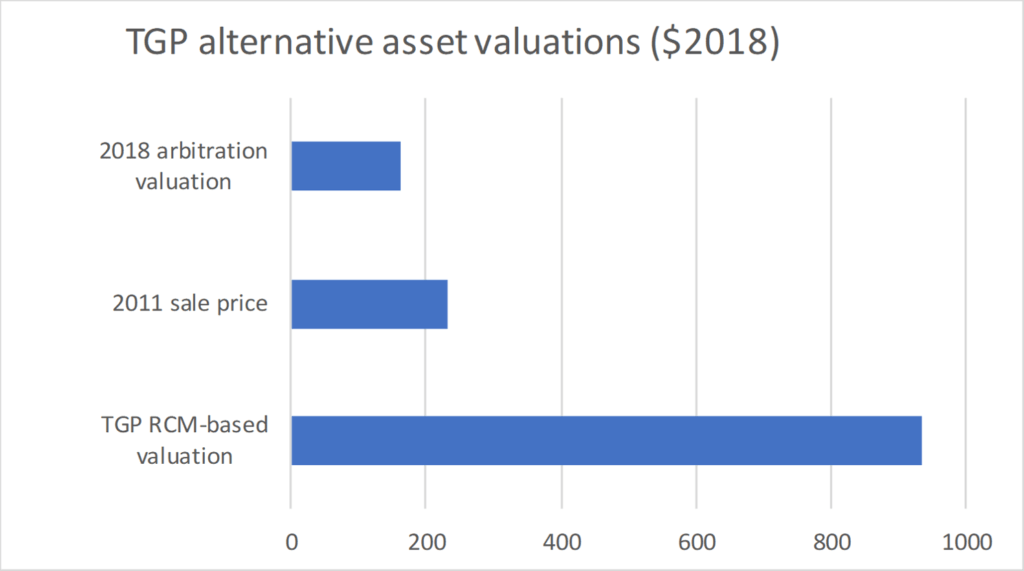

The first and only access dispute so far under Part 23 occurred in 2018, involving the Tasmanian Gas Pipeline (TGP), illustrates starkly the inconsistency of RCM with a workably competitive market outcome. The graphic below shows three very different publicly available asset valuation outcomes for TGP.

The different valuation outcomes are as follows:

It is worth noting the original construction cost of the pipeline in 2002 was $441.2 million ($2002).

Clearly, the RCM valuation was of no assistance to the arbitrator. Interestingly, the 2011 sale price is much closer to the value the arbitrator ultimately adopted. This is not surprising as it incorporates a purchaser’s view about future demand for the pipeline’s services (albeit in 2011), influenced by the then expected revenue earning potential of the pipeline, particularly from existing contracts.

In looking for ways to drive down the delivered cost of gas in a supply constrained environment, policy and rule makers do not appear to fully understand the implications of applying the RCM.

Its application will lead to asset valuation and price outcomes contrary to workably competitive market outcomes, making it inconsistent with the objective of Part 23. Hence, it is difficult to see how the RCM could be applied in any future arbitration dispute and meet the workable competition objective.

Given the problems identified with its use, the review of Part 23 currently being undertaken by the COAG Energy Council provides an appropriate opportunity for the RCM’s removal from the NGR.

Ironically, the impact of RCM for new pipeline investments is also perverse, as it encourages pipeline owners to recover the full capital cost of their pipelines from foundation shippers to minimise the capital recovery at risk in the future. This may generate lower pipeline charges in the very long term but will increase tariffs (and probably reduce contractual flexibility and prolong foundation contracts) in the short term, contrary to the underlying objective of Part 23 and the long term interests of gas consumers.

[1] Non-scheme pipelines are distribution and transmission gas pipelines that are not subject to either full regulation (Part 9) or light regulation (Part 7) under the NGR.

[2] The closest valuation approach to RCM that we are aware of is generally known as ‘loss capitalisation’, whereby Australian economic regulators in rare cases have allowed utilities to capitalise short term revenue shortfalls (relative to allowable revenue) in the regulatory asset base under the key assumption that longer term demand will be sufficiently strong to allow recovery of these capitalised shortfalls. Importantly, loss capitalisation has always been applied ex ante and transparently by the economic regulator rather than ex post as was the case with the RCM.